Penn Station Rebuilding Resembles Game of RISK with Feuds and Alliances Forming

Shifting alliances appear to be forming behind the scenes in the fight for the future of Penn Station. There are still parties who want to give Madison Square Garden the ol’ heave ho from atop the nation’s busiest rail hub while others think a public private partnership involving a private developer that keeps in MSG atop a new more open Penn Station works just fine.

Building in New York is never simple.

New York is now witnessing the extraordinary spectacle of public agencies fighting to keep control of a public project. The struggle over how to rebuild Penn Station has devolved into an extraordinary competition between the railroad giants who use it, and have a master plan to fix it, and a private developer from Italy that says it can do better.

The Italian company, ASTM, a specialist in developing highways and other public infrastructure, has mounted an intensive lobbying campaign for its plan, noteworthy both for winning important supporters and for more or less blowing right through the process the railroads had created to design and execute their plan.

As ASTM has lined up increasing support, the railroads, led by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, have become increasingly vocal in their criticism.

“The ASTM idea to add $1 billion to $2 billion to the project cost for an 8th Avenue train hall that includes a payout to Madison Square Garden is not appealing,” The MTA’s Chief of External Relations, John J. McCarthy, said in a statement to Straus News. “Since focus needs to be on creating an inviting and safe public transit experience for all riders while keeping costs down.”

“The MTA is working with partners Amtrak and NJ Transit to move forward with a master plan for Penn Station which will fix the iconic terminal for its hundreds of thousands of daily riders,” said McCarthy.

Last September the railroads announced, after a competitive bidding process, the selection of a design and engineering team for their master plan, FXCollaborative Architects LLP and WSP USA Inc., with John McAslan + Partners serving as a collaborating architect.

McAslan is well known for his renovation of London’s Kings Cross station, including the installation of skylights that helped transform the dingy station into a sun-filled transit hall. A consummation devoutly wished for by the 600,000 riders who use Penn Station.

But even as the railroads were conducting the competition to find their architects and engineers, ASTM was working independently on its own plan.

Public word of ASTM’s project only emerged last March, six months after the railroads appointed their architects, but the firm is said to have been developing the project for three years, although it apparently chose not to compete in the bidding process the railroads conducted.

ASTM’s North American branch, which is run by a former head of the MTA, Pat Foye, have been working tirelessly behind the scenes to line up support. Among those who have endorsed at least the outlines of the ASTM plan are the Borough President of Manhattan, Mark Levine, and the head of the Municipal Arts Society, Elizabeth Goldstein.

There are three big differences between the MTA master plan and the ASTM plan.

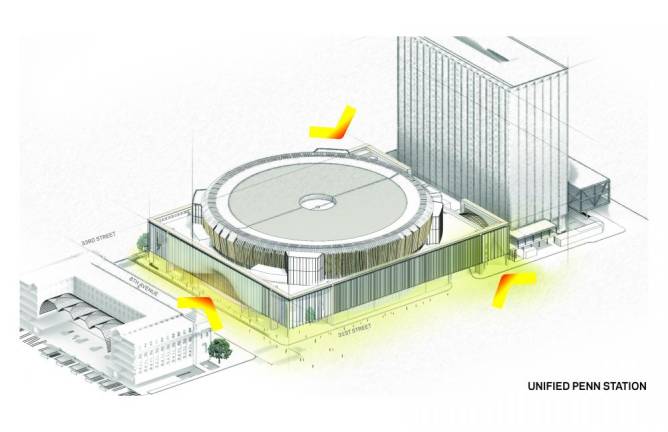

The first is that the ASTM plan would demolish the Madison Square Garden Theatre on the western edge of Madison Square Garden and use that property to build a large entry way and train hall from Eight Avenue.

A second is that ASTM would pay Madison Square Garden a lot of money -- they have not publicly said how much -- for that theatre and other property needed for its plan, including the taxiway along the east side of Madison Square Garden.

In contrast, The MTA plan would pay Madison Square Garden nothing for the taxi way and other properties, including at the corners of Eight Avenue and 31st and 33d streets, for its versions of improved Eight Avenue entry ways.

In exchange for the taxiway and eight avenue property, the MTA master plan does offer to “swap” some property which is currently part of the Station, which is owned by Amtrak, so Madison Square Garden can improve its loading facilities and get some of the tractor trailer trucks off the streets.

The MTA master plan also asks The Garden to pay some construction costs in situations were both the station and the Garden will benefit from the improvements, such as the expanded entrances at the corners of the station on Eighth Avenue .

The other major difference is that ASTM would pay for the property purchase and construction out of capital they raise privately, recouping their investment over many years from payments from the railroads. The federal government allows certain federal infrastructure payments to be used to fund these so-called Public Private Partnerships.

ASTM’s engineering partner in its Penn Station plan is HOK, which co-designed the successful Terminal B at LaGuardia Airport. “In the spirit of grand transportation centers like New York’s celebrated Grand Central Terminal, the new Terminal B ushers in an ambitious new era of mobility and travel,” HOK says of its new airport terminal. “Its verticality and scale echo the grandeur of the city itself.”

HOK is already working with the MTA on its so called Penn Access project, which will bring metro north trains into Penn Station.

Much of what we know about the competing plans for Penn Station was brought into public view at a hearing by the City Planning Commission. Ironic, since the hearing was not actually about either plan.

It was about whether to extend the special permit Madison Square Garden is required to have to operate an arena in New York City larger than 2,500 seats. The Garden was granted this permit when the Pennsylvania Railroad, struggling financially, tore down its legendary station and sold the street level property to The Garden, which had been on Eighth Avenue and 50th street.

Advocates for building a new above ground station want to use this permitting process to force the Garden to move. The MTA and the other railroads adopted a different approach, asking the planning commission to get the Garden to negotiate with them to cede property rights and agree to pay some of the reconstruction costs to improve Penn Station with The Garden still on top.

This infuriated the Garden, which at one point during the hearing said if it did not get its permit it had the right to just build an office building on the site, which it owns from the street up.

Dan Garodnick, the chair of the planning commission, said that extension of the Garden’s operating permit would be contingent on the Garden showing it was cooperating in a plan to improve Penn Station, but he did not specify which plan.

It became clear during the hearing that The Garden has been working closely with ASTM on engineering details of its plan. This raised the obvious question of when The Garden and ASTM began collaborating.

Madison Square Garden declined to discuss the details of its relationship with ASTM, other than to say, as it has many times: “As invested members of our community, we are deeply committed to improving Penn Station and the surrounding area, and we continue to collaborate closely with a wide range of stakeholders to advance this shared goal.”

ASTM officials have said in presentations to community leaders that they came up on their own with the idea to develop a Penn Station project.

“It was a total self-starting project,” one community leader quoted the ASTM officials as saying. “They were not solicited by anyone.”

Vishaan Chakrabarti, an architect who had long called for Madison Square Garden to move, told the Architects Newspaper last month that at a meeting with ASTM and HOK this year he discovered that they had been partnering with Garden staff for over a year, while “no one in government had approached the Garden about moving whatsoever.”

He told the newspaper this catalyzed his decision to embrace the ASTM plan as the best achievable version of a new station without moving the Garden.

One of the political headwinds the railroads are facing for their master plan is the way it had been tied by governor Hochul, and Governor Cuomo before her, to a massive redevelopment of the surrounding neighborhood. The state had been planning to siphon revenue in lieu of property taxes from new office towers to help pay the state’s share of the Penn Station reconstruction costs.

That plan however is in limbo because the principal developer, Vornado Realty Trust, has said market conditions are not conducive to building more office towers.

Hochul has said she has other options for revenue but has yet to identify them. ASTM’s plan would pay the immediate costs out of their private capuital and push costs to the state well into the future.

In the meantime, Hochul has sought to project strong momentum on the repair of Penn Station. The announcement that the railroads had hired a team of architects and engineers was expedited to show motion before Hochul’s reelection last fall. But in fact the architects and engineers have not actually begun work yet because the MTA and Amtrak had still been negotiating the plans, officials reported.

“The initial Master Plan study has been completed,” said Amtrak spokesperson, Jason C. Abrams. “We are looking to proceed this year.”