Hop Over to the Morgan to See “the Other Potter” Who Created Peter Rabbit

“Beatrix Potter: Drawn to Nature” is at the Morgan Library & Museum, 225 Madison Avenue (at 36th Street); through June 9. www.themorgan.org

Potter fans have been crowding an elegant gallery space in Manhattan for a delightful show about the author of a celebrated book series geared to young people. But we’re not talking about the woman who spun tales of wizards and broomsticks and a boy named Harry. We’re talking about that other Potter–Beatrix Potter (1866-1943)–whose letter to a child about a bad bunny named Peter became the touchstone for the classic story, “The Tale of Peter Rabbit.”

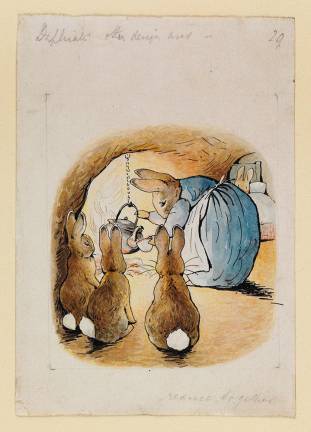

The Morgan Library & Museum at 225 Madison Ave. is staging the exquisite show, “Beatrix Potter: Drawn to Nature,” through June 9. It was created by the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and comprises drawings, watercolors, books, letters and artifacts (her paintbox, her clogs, her handkerchief) sourced from select British institutions and the Morgan’s own collection of Potter’s picture letters.

About half of the nearly two dozen tales about errant rabbits and dressed up mice, frogs and squirrels are based on illustrated letters Potter sent to children. Viewers on a recent visit were huddled around that seminal missive created in 1893 for Noel Moore, son of Beatrix’s former governess, featuring Peter Rabbit and Flopsy, Mopsy and Cottontail.

Noel’s mother sent the enchanting letter back to Potter eight years later so she could copy it and monetize it by turning it into a book. As curator Philip Palmer says in a video presentation about what he terms “the origin story”: “Potter always said this book was successful because ‘it was written to a child, not made-to-order.’”

While Beatrix Potter is a household name known primarily for her neatly packaged books about animals with playful names that act and dress like people, most are probably unaware she had a keen interest in natural history and the environment.

In a letter written shortly before she died, she stated, “I do not remember a time when I did not try to invent pictures and make for myself a fairyland amongst the wildflowers, the animals, fungi, mosses, woods and streams, all the thousand objects of the countryside...”

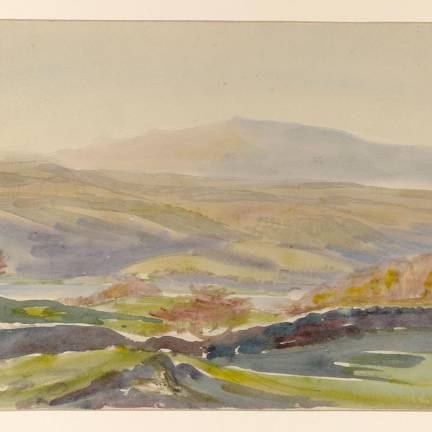

Her interest in nature started during childhood when she and her brother Bertram had a nursery with a slew of pets including dogs, salamanders, hedgehogs and even bats and rats. And of course, the menagerie also included two bunnies, Benjamin Bouncer, the model for Benjamin Bunny, and Peter Piper, the model for Peter Rabbit. After she became a popular author as an adult, she bought a farm, Hill Top, in Cumbria in 1905 and became a Herdwick sheep breeder and fell farmer. By the time she died as a wealthy author, she bequeathed more than 4,000 acres, including 14 farms and 60 other properties, to the UK’s National Trust.

Palmer notes Potter’s study of botany, insects and mycology, in particular, as leading to a wealth of scientifically accurate drawings of mushrooms and animal and plant life, which fed her story art. Her walking stick, on view, was embedded with a tiny microscope to allow for careful observation of flora, fauna and fungi. The curator advises viewers to consider “particularly how the stories behind the books evoke a sense of place and environment.”

There are several miniature letters on display that the author composed for children in the voice of her storybook characters, Squirrel Nutkin and Old Brown, the owl from “The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin.” She would write other such mini missives to children in the voice of other book characters and address them to imaginary places such as “Mouse Hole” or “Barn Door” because she was a writer who embraced the concept “small is beautiful.” Per a picture letter here that she wrote to a child in 1900 in which she recounts a contretemps with a publisher over the size of her books, she advocates for “little books” that “little rabbits” could afford.