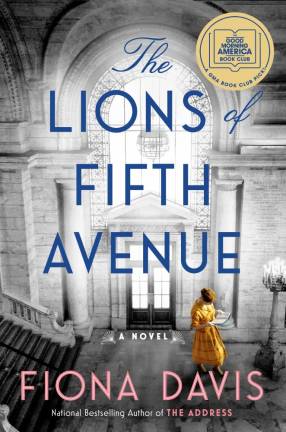

A common and captivating thread in all of Fiona Davis’s novels is that they are centered around one of Manhattan’s many iconic buildings. From Grand Central Terminal to the Dakota to the Chelsea Hotel, her books skillfully use the buildings to tell the stories of fictional characters whose lives are part of the landmarks’ rich histories.

Upon her research on the New York Public Library, a frequent suggestion from her loyal fanbase for the setting of a future work, Davis discovered that there had been a seven-room apartment inside that housed its superintendent and his family. This fascinating fact became one of the backdrops for “The Lions of Fifth Avenue,” which interweaves the story of the fictional wife of the superintendent in 1913 with her granddaughter’s, who serves as a curator at the library in 1993.

The Canadian-born Upper West Side writer has her own history with the library. When she first arrived in New York as an actress with a theater company, her earliest experiences in the library involved referencing its picture collection to research costumes for different period pieces. In her next career as a student at Columbia Journalism School, she would research articles there. Now, she uses the Allen Room, reserved for authors with book contracts, to pen her stories. “It was amazing to be able to write about the library in the library. It was an incredible experience.”

The library’s superintendent and his family lived in an apartment there. What did you discover about them?

His name was John Fedeler and he lived in the library with his wife and three kids. They moved in a little before it opened and were there for 30 years. There were some articles in the New York Times about him. His son went on to become chief engineer of the library and his daughter was born in the library. They used to play baseball using books as bases in the Reading Room until they got in trouble. [Laughs] It’s really pretty amazing, the idea of this family tucked away in the library. So it was fun to incorporate that into the book.

There were so many interesting facts in your book about the library’s architecture. In your acknowledgements, you mention architectural historian Francis Morrone, who I also interviewed for this column.

Isn’t he brilliant? He’s just a treasure of New York. It was built by Carrere and Hastings, who are quite renowned. It took nine years and nine million dollars to build. And I love that they did not only the building aspect, but all of the details, like the desks. If you look at them carefully, they’re intricately carved. And the wastebaskets and the lights, there was really no detail that they did not address in some way. I think that makes the building a real cohesive whole, and that’s one of the reasons it’s so spectacular to walk through.

You graduated from Columbia Journalism School. What was that experience like and why did you want your character, Laura, to attend there as well?

As I was doing research, I knew I wanted it to be set in the 1910s. It turned out on a timeline I saw that the journalism school opened in 1912. And I just thought, “Oh, that’s fantastic.” It was co-ed; it was only 15 percent women at that time. There’s a wonderful book, “Pulitzer’s School” by James Boylan, about the history of the school that I pulled a lot of the stories from about how women were sent to [cover] different stories than men. Women didn’t cover politics or murder; they covered poverty in the tenements. I had an amazing time at the school. It really taught me how to think and tell a story. These days, Columbia Journalism School is 75 percent women, so it has changed a lot.

Your protagonist from the 90s, Sadie, is a curator of the library’s Berg Collection. Tell us what you learned about that area.

It’s like a library within a library. You can’t just walk in; you have to apply to go in and show that you’re a researcher or scholar. It has rare books, manuscripts, diaries, and letters from over 400 authors. It really is just this treasure trove of items that help illuminate how these great writers who we revere, thought. There’s a draft of a Walt Whitman poem that really shows his thought processes as he created it. There are lots of things scratched out and written over. It’s just a wonderful way to see how this poem evolved. Then they have Jack Kerouac’s boots and Virginia Woolf’s walking stick that she left by the river before she drowned herself. And they have this amazing cat paw letter opener that was Charles Dickens’. He had this beloved pet and had its paw made into a letter opener after it died.

Give us one interesting fact from each of the buildings you wrote about in your five novels.

With each building, there’s something that surprises me, and that’s what I build the story on. So for Grand Central Terminal, it was the fact that there was an art school deep within the terminal. It was there for decades and had 900 students a year. It was called Grand Central School of Art and no one had ever heard of it.

For the Barbizon Hotel for Women, the surprising fact was that when it went condo, there were a dozen of the old-time residents who’d been there since it was a hotel, living there, grandfathered into rent-controlled apartments on the fourth floor. I loved that idea of these women who’d been there for years, meeting the current residents, and what that dynamic was like.

For the Dakota, in the basement, there’s a room full of claw-footed bathtubs, pocket doors, and fireplace mantels, because if anyone ever renovates, they save all of the original details and keep them safe.

Then there’s the Chelsea Hotel, which is filled with ghosts. I talked to a woman who had written a nonfiction book on the hotel that had all this detail about the ghosts, and it’s pretty well documented. Lots of people have talked about them.

The new book is also part mystery, focused on uncovering book thefts. That was inspired by a real-life theft at Columbia’s Butler Library.

In 1994, a thief stole 1.8 million dollars [worth] of rare books and manuscripts from the university’s library over a period of three months. And no one could figure out how he was getting in and out. And the answer was really kind of shocking, and so I used that as the idea for my theft in the New York Public Library, where that did not happen. It was just a terrible theft that really was damaging, but luckily, they were able to find the thief. And then the chief librarian went before the judge and asked for a harsher plea, and because she was so passionate about the damage that he’d done and why rare books are important, the judge gave him a harsher sentence.

www.fionadavis.net